ARTicles

A Tale of Two Books

Turning the clock back to the early days of watercolour paints and pigments.

The first commercial European watercolours were produced in the eighteenth century and consisted of a hard block, which required considerable rubbing to dissolve in water. With the invention of the collapsible metal tube in the mid-nineteenth century, it allowed art material manufacturers to supply watercolour paints in liquid form, which made the medium easier to use and so helped to increase its popularity. At the forefront of this watercolour revolution was the scientist, William Winsor and artist, Henry Newton, who together began to modernise the craft of the Colourman and lay the foundation of modern artists’ colour manufacture.

Winsor and Newton recognised the need to grow their business on the foundations of science, so in 1854, William Winsor bought the rights to George Field’s “A Treatise on Colours and Pigments, and their Powers in Painting”, along with his chemical process to synthesise pigments from the madder root (W&N). Here begins our tale of the first book.

Field’s Chromatography:

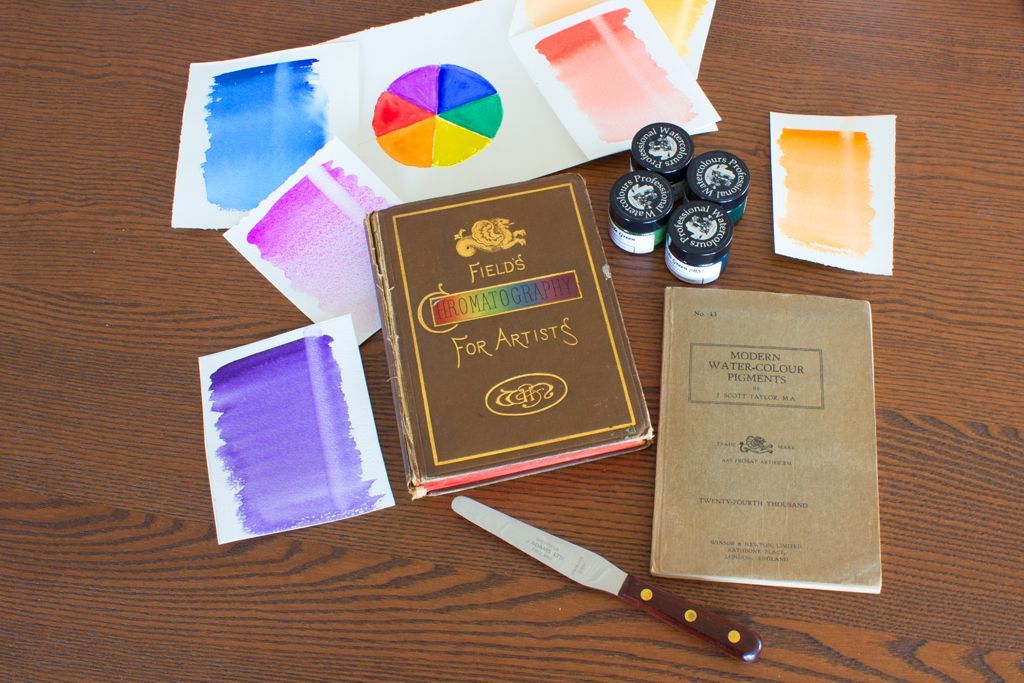

Figure 1: Field’s Chromatography, the third edition, published in 1885 by Winsor & Newton

George Field was an English chemist, who is best remembered for his book on colours and pigments, which had been originally published in 1835 (Wikipedia). It became known as “Field’s Chromatography” and it is the culmination of his many years of colour experiments and manufacture. Amongst art historians it is regarded as a seminal nineteenth-century text on colour theory, which help shape the course of British painting. While Field’s colour theories dated very quickly, the detailed information he shared, concerning the available colours and pigments available, was priceless to the artists at that time. The information he provided included which pigments were lightfast and durable and warned, which ones were not (Shires).

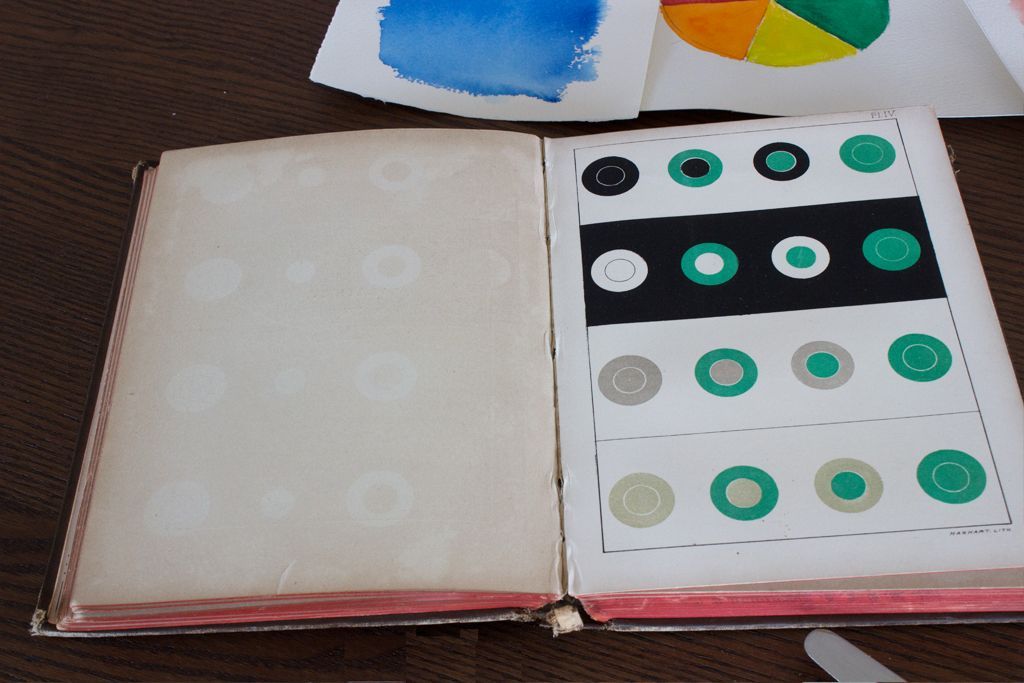

Figure 2: A glimpse inside Field’s “Chromatography” at one of the colour plates.

“Field’s Chromatography” was later republished in 1869, edited by T W Salter and again in 1885, modernised by J S Taylor, both times by Winsor & Newton. It is interesting to note that the T W Salter edition was published after William Winsor’s death in 1865, obviously supported by the surviving partner, Henry Newton, who like George Field, felt it necessary to provide the artist with information on the theory of colour and the pigments used.

The third edition, the one I have, was published after the death of Henry Newton and the formation of Winsor & Newton Ltd in 1882, showing that the new management though in a similar way to their predecessor.

For me, this book is invaluable, in that it sheds light on which pigments were found in the classic artists’ colours, which helps me to ensure that my Professional Watercolours have their roots in the traditional and classic ones developed in the mid-nineteenth century. It gives me confidence that my watercolours have authenticity and I can trace their lineage back to source, rather than down a well-trodden path that may not be completely in the right direction.

When I was an integral part of Winsor & Newton in the late 1990’s, I learnt the importance of heritage and the role it plays in the relationship between colourman and artist. It forged and distilled my own ideas of what I should offer my own artists; attention to detail being one of them and a grounding in tradition, another. It was with this in mind that I sought the second book in our tale.

A Descriptive Handbook of Modern Water-colour Pigments:

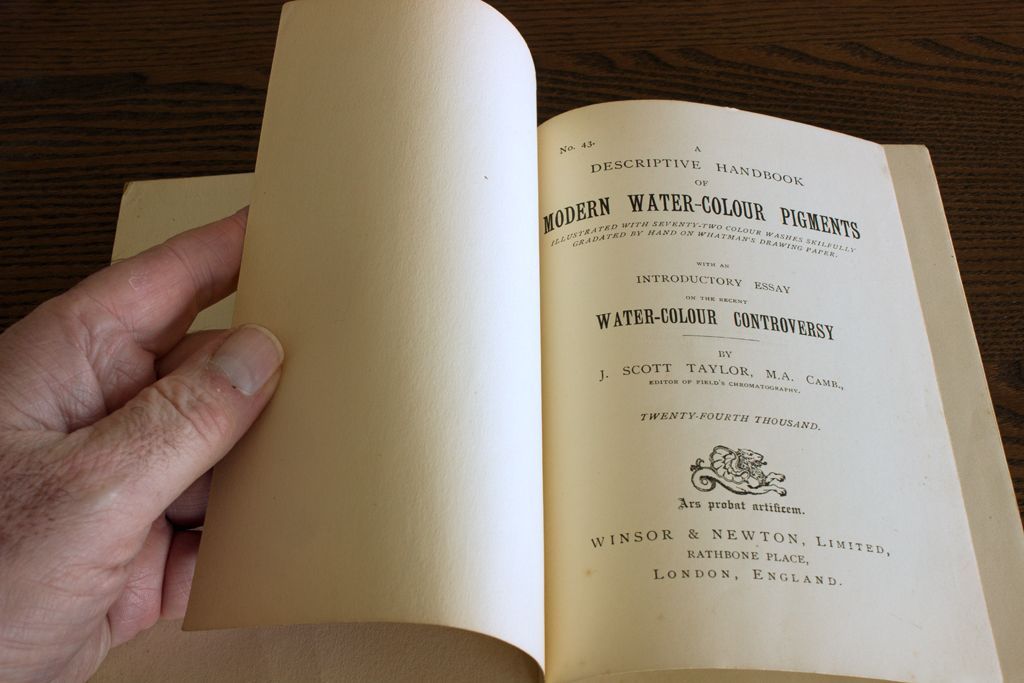

Figure 3: John Scott Taylor’s descriptive handbook, which is truly a glimpse into watercolour pigments of the past.

As with the third edition of Field’s “Chromatography”, J S Taylor’s “A Descriptive Handbook of Modern Water-colour Pigments” was published by Winsor & Newton. When it was first published in 1887, the credibility of watercolour as a serious art medium was in question due to the use of fugitive pigments. In answer to this the first section of J S Taylor’s handbook deals with questions about the long-term effect of light on watercolour pigments, which is further developed in Taylor’s descriptions of each pigment in section 2.

Figure 4: The “controversy”

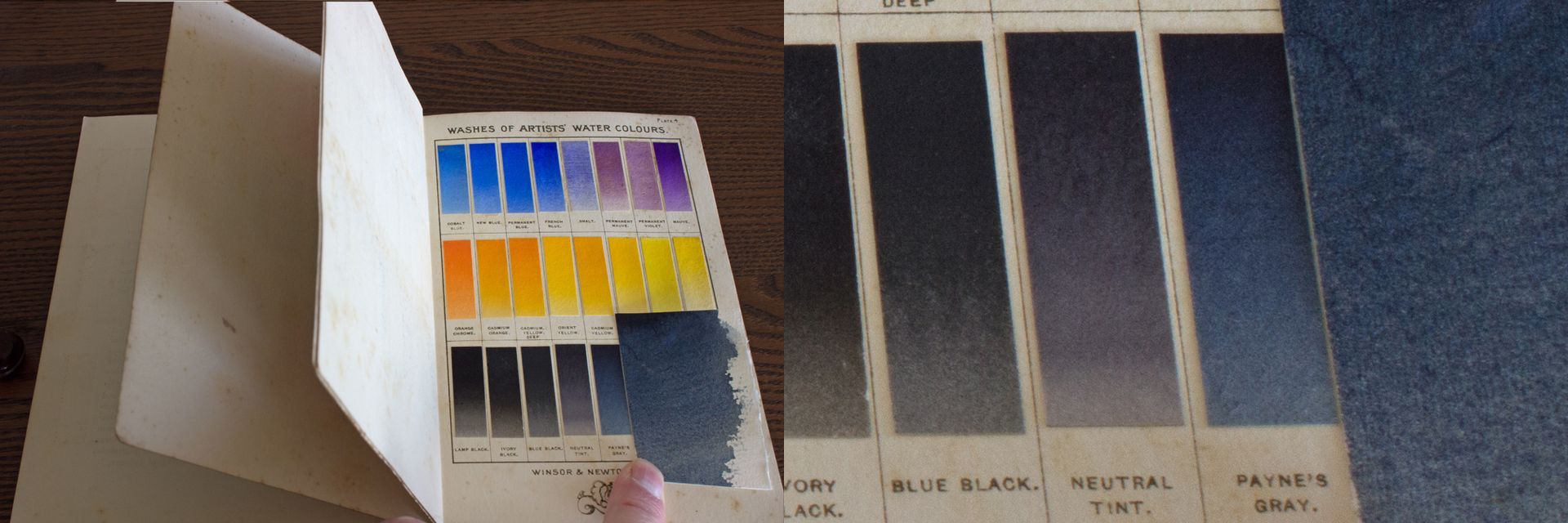

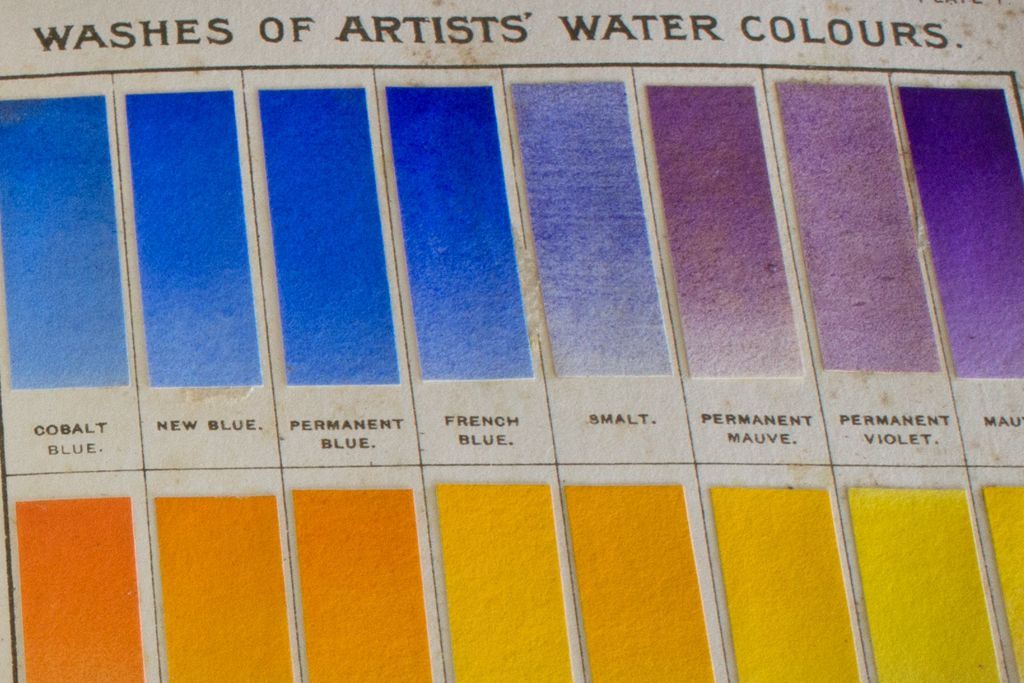

However, located at the end of the edition of this book I have, is a 110 watercolour washes hand pained on Whatman paper at the time of publication, and they are as fresh as the day they were painted (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Hand painted watercolour washes.

Using this edition of Taylor’s handbook, I can check the colours of my watercolours with those made in the late-nineteenth century. In figure 6, I am comparing my Hooker’s Green No1, whilst in figure 7, my Payne’s Grey is almost identical to those preserved in the descriptive pigment handbook.

Figure 6: Hooker’s Green No1.