ARTicles

Adding life and movement to paintings by introducing supplementary figures.

Believe it or not, producing convincing figures is not as straight forward as one would think, but with practise and a trained eye, the task becomes easier and the results can turn a static image into a painting full of life and activity.

I have found that introducing supplementary figures into a painting changes the whole dynamic, it can turn an otherwise “flat” or seemingly “static image” into one that seems to depict life and movement. A painting of a desolate beach can go from just another painting of a delightful beauty spot to an interesting and captivating day at the seaside, just by adding a few figures.

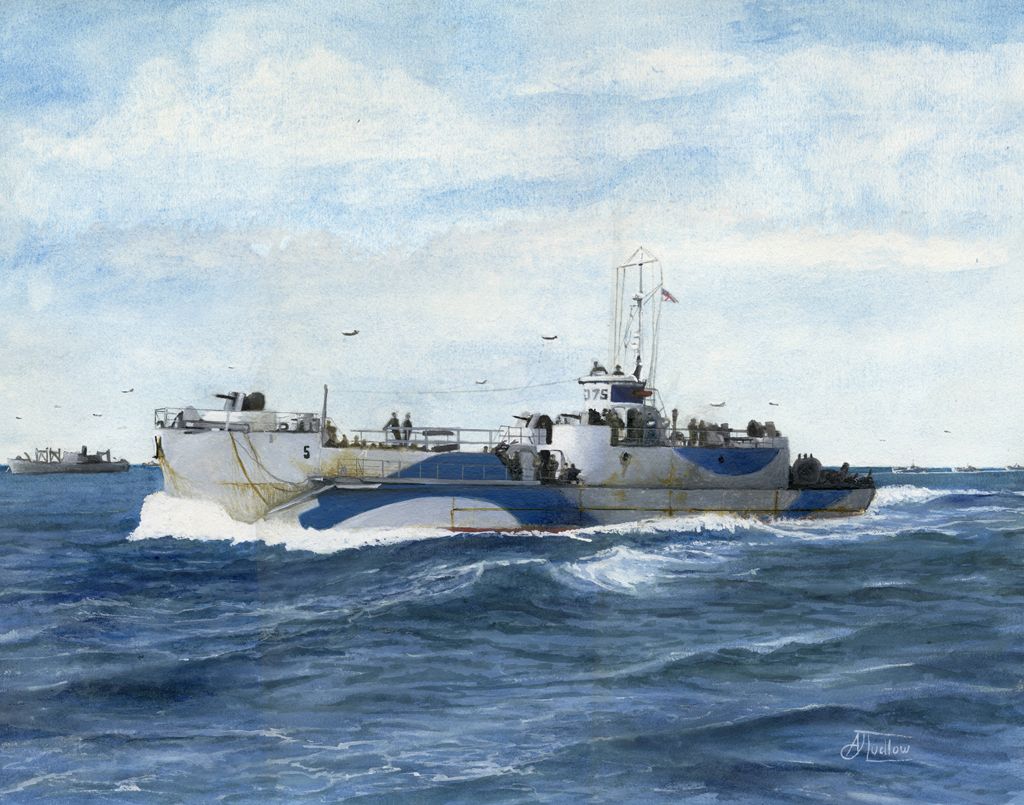

In my painting “Landing Craft Infantry 375” (see figure 1), I carefully included the numerous personnel who were on deck at the time when the original photograph was taken and included a few others, when it was difficult to make out exactly what the image was showing. In the painting, the figures are hard to notice and do not stand out, because they have a natural synergy with the rest of the painting. That is why I used the phrase “carefully included” as the result could have been very different.

Figure 1: “Landing Craft Infantry 375”, a watercolour painting by Andrew Ludlow

To leave the figures out would obviously have been easy to do, but the bridge and deck would have been empty and I am sure that would have given the painting an un-natural feel, as the craft is under full speed, heading for the Normandy coast on the morning of D-Day. So, adding the figures was certainly necessary. However, just by adding a few unconvincing figures would equally have create an un-natural feel and look about the painting.

So, what is a supplementary or synergistic figure in a painting, how can it be created and more importantly, what is an unconvincing one and how can they be avoided?

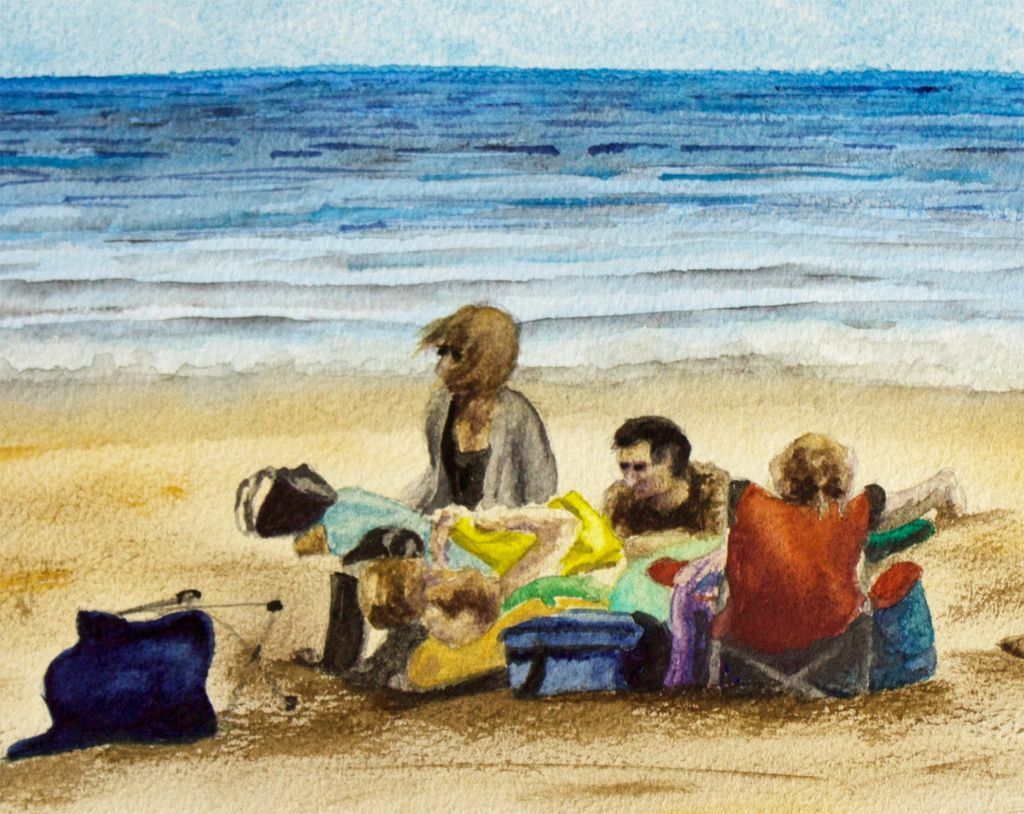

The beach scene in figure 2 is a detail from an abandoned watercolour painting and is a good example of getting it wrong and creating unconvincing figures. It shows a family on a wind-swept beach; an over turned deck chair and the woman’s hair provide movement, the posture of the figures is what you would expect from a family trying to shelter from the wind, but there is something visually that is not quite right. The woman and man are the focal point and this was true for the whole painting, because the figures look un-natural and stick out. It is not just a matter of making sure that the subtle nuances of the human form are accurately depicted (and so avoiding distorted or wooden figures), too much defined detail can also have an impact too, as in the case of this painting. My opinion as to why this grouping did not work is because the man’s face and the woman’s sunglasses are too well defined.

Figure 2: Detail from an abandoned watercolour painting by Andrew Ludlow.

It follows then that a convincing figure is one that is in harmony with the rest of the painting, as in the case of the figures on the deck of “Landing Craft Infantry 375” (shown in detail in figure 3). What is evident with these figures is that their stance, posture and shape are accurately depicted in the painting but there is very little defined detail, which is correct, as the craft is some distance from the observer. Forgive me for stating the obvious, but the rules of perspective and distance must apply to the figures equally as it does to the surroundings.

Figure 3: Detail of the figures on the deck of “Landing Craft Infantry 375”.

In the watercolour painting “Miss Lace Receives Some Tender Loving Care”, the Boeing B-17G (42-97976) “Bit o‘ Lace” is being repaired/serviced in a hanger by USAAF ground crew (figure 4). What makes this painting so interesting is the ground crew going about their jobs repairing the aircraft.

Figure 4: “Miss Lace Receives Some Tender Loving Care”, a watercolour painting by Andrew Ludlow.

The painting works well because the figures are accurately depicted, with the right amount of definition (see figure 5). Again, the incidental figures are in synergy with the rest of the painting.

Figure 5: Detail from “Miss Lace Receives Some Tender Loving Care” by Andrew Ludlow.

Likewise in the oil painting “Great Yarmouth 2” (figure 6), the figures show just the right amount of definition, even though they are the focal point of this colourful hot summer afternoon on the beach at Great Yarmouth in Norfolk.

Figure 6: “Great Yarmouth 2”, an oil painting by Andrew Ludlow.

To create convincing figures is not a difficult task, but can be fraught with frustration. To succeed requires a concerted effort in observation and practice.

A big generalisation here: everyone knows that formal art training includes life drawing, working from the nude figure as a means of observing and understanding the nuances of the human form and thus develop the untrained eye into one that can detect the subtleties of the human figure at rest and in motion and so be able to depict it in their work with convincing accuracy. I think the important aspects here are observation and the existence of the untrained eye.

I read an article a long time ago in one of the painting magazines by Gerald Green (unfortunately I no long have the reference, but do have a photocopy to refer to), who suggested keeping a sketch book of drawings made of people going about their day. He recommended that the sketches be quick, with the minimum amount of drawing but a lot of observation. He would then use these studies to add figures to his own paintings. He also suggested experimenting by making, what he called brush “doodles”, which I have followed and the results are shown in figure 7.