ARTicles

Further Reflections on Whether Traditional Chinese Painting Brushes are suitable for Watercolour Painting.

Following on from last month’s ARTicle, we look to embrace the qualities of traditional Chinese Painting brushes and see what they can do for our watercolour painting.

After the “cliff hanger” of an ending to January’s ARTicle, “Are Traditional Chinese Painting Brushes suitable for Watercolour Painting?”, I waited with “bated breath” to see if the oldest member of the “Four Treasures of the Study” could be used to paint watercolours. Hopefully this was also true for you, the reader.

In last month’s ARTicle, I demonstrated that each one of the chosen Chinese brushes formed a point when dipped into water and so springing back into shape. This indicated to me that the hair was of a high standard and had been dressed skilfully during the brush making process and thus meeting two of the criterion that we watercolourists are looking for in a brush. The other criteria I considered in that ARTicle included the ability of the brush to “hold and release” water and distribute the watercolour evenly on the surface of the watercolour paper, which I stated, contributed to the suitability of the brush for painting out free flowing water-based paint. It is these criteria that I shall use to assess my selected Chinese brushes in this month’s ARTicle.

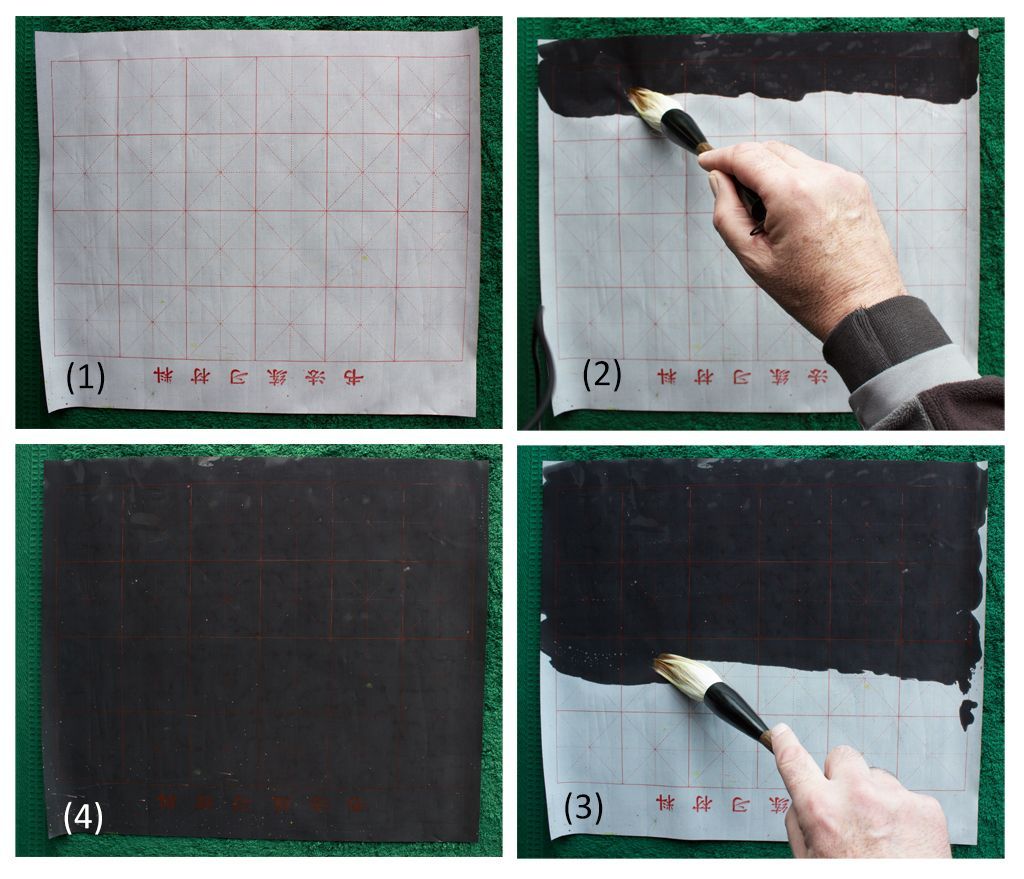

To assess and show the brushes’ ability to “hold and release” water, I decided to use a Brush Art practice cloth, which changes colour when it is wet and can be re-used over and over again once it has dried. It is commonly used in Chinese schools to practice calligraphy and perfecting brush strokes for Chinese painting and is considered eco-friendly as it requires only clean water to create a mark. With regards to the size of cloth I used and to provide a frame of reference for the following photographs shown in figures 1 to 6, the cloth measured 41 x 35.5 cm, thus giving a surface area that’s approximately 17% larger than a sheet of A3 paper.

I performed the test by allowing the brush to pick up its fill of clean water, removing any excess droplets, by gently touching the brush hairs to the water container’s lip, and then with a single stroke, paint the surface of the practice cloth until the brush become dry.

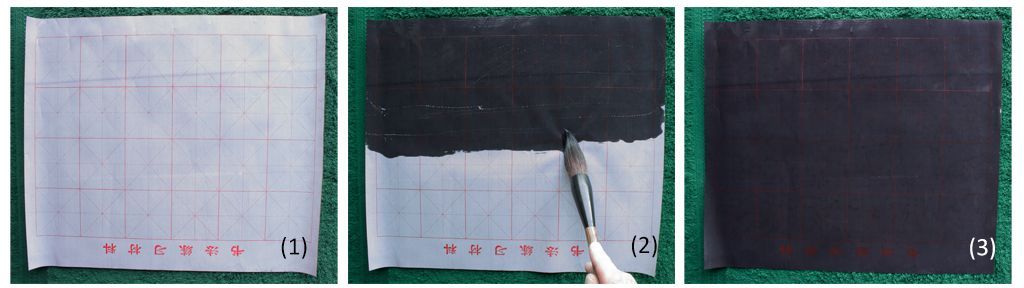

Figure 1: Painting out using a large calligraphy brush made from a combination of yellow weasel hair surrounded by white goat hair; the process follows from (1) clean dry practice cloth, to (4) completely covered.

Figure 2: Painting out using a large calligraphy brush made from pure black rabbit hair; the process follows from (1) clean dry practice cloth, to (3) completely covered.

The results obtained using the large calligraphy brushes (figure 1 and 2), show complete coverage of the practice cloth (approximately equivalent to a flat wash over an area larger than A3) in a single stroke. After painting out, the mixed hair brush still contained a lot of water, whereas the rabbit hair brush was reaching its limit.

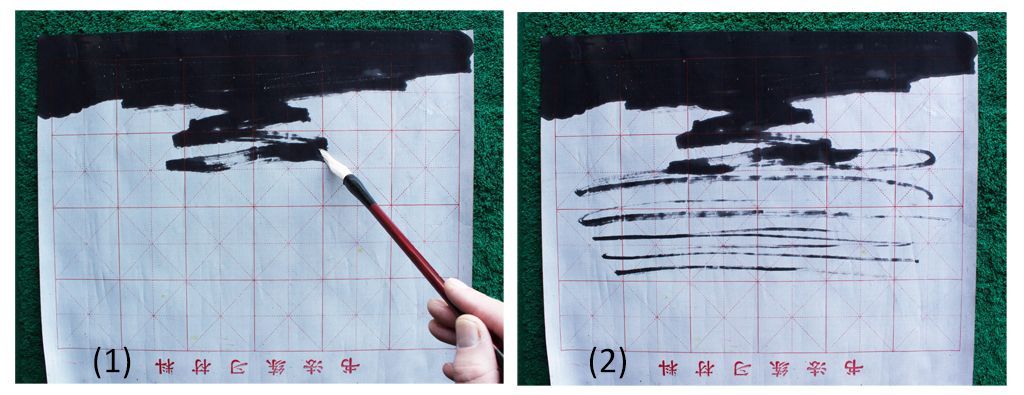

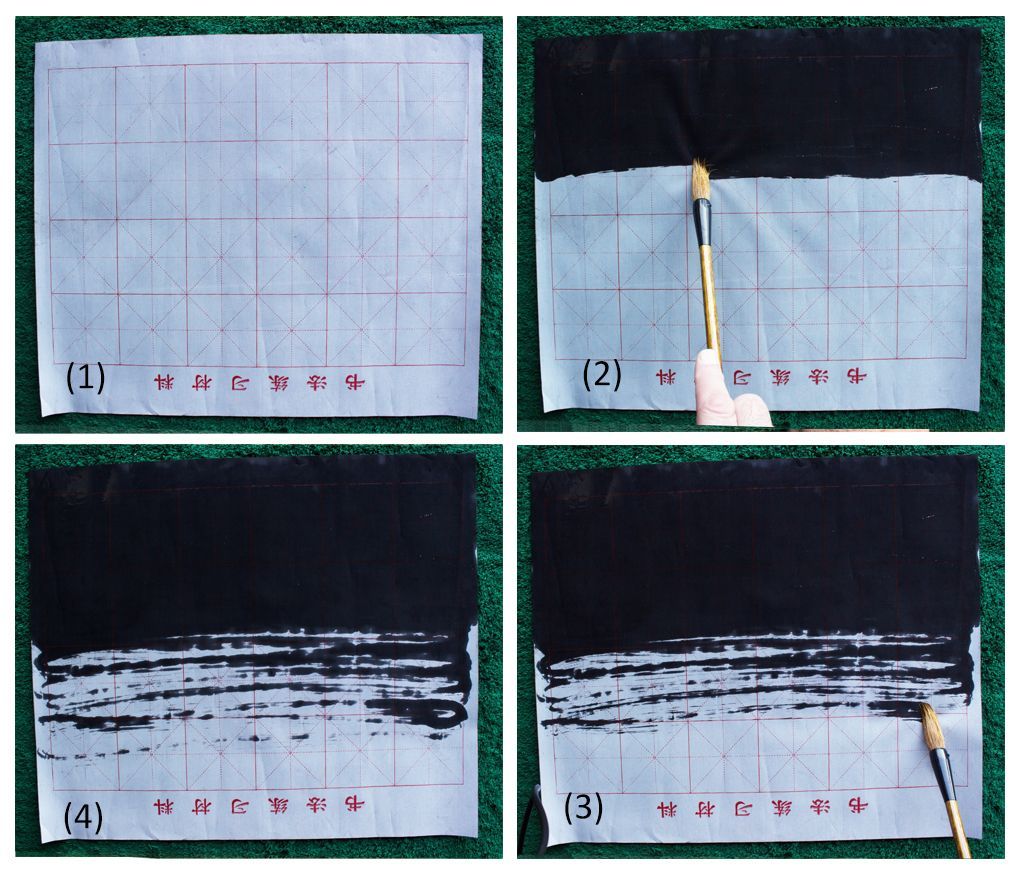

Figure 3: Painting out using a large painting brush made from a combination of black rabbit hair, surrounded with white goat hair; the process follows from (1) clean dry practice cloth, to (4) where the brush became dry.

Figure 4: Painting out using a medium painting brush made from a combination of black rabbit hair, surrounded with white goat hair; the process follows from (1) clean dry practice cloth, to (3) where the brush became dry.

The brushes in figure 3 and 4 are made in an identical fashion, except the one used in figure 3 has a larger head and so has more hair. The amount of coverage in figure 3 when compared to figure 4 is approximately twice. In my opinion, both brushes hold a fair amount of water, which could deliver a good deal of watercolour in one stroke.

Figure 5: Painting out using a medium sized painting brush made from white goat hair.

The medium sized white goat haired painting brush (shown in figure 5) did not hold as much water as the medium sized one in figure 4. This may be due to the combination of hair used in the brush, helping the water to flow out better than the pure white goat haired one. Both brushes are capable of drawing fine lines, as can be seen in figure 4(3) and 5(2), which would be beneficial for intermediate detail and where fine control is needed.

Figure 6: Painting out using a large painting brush made from yellow weasel; the process follows from (1) clean dry practice cloth, to (4) where the brush became dry.

The yellow weasel brush used in figure 6, has a similar sized head to the combination brush used in figure 3. From the markings on the handle, the brush is actually a small sized calligraphy brush and as such holds a reasonable amount of water (which appears to be slightly more than the brush in figure 3).

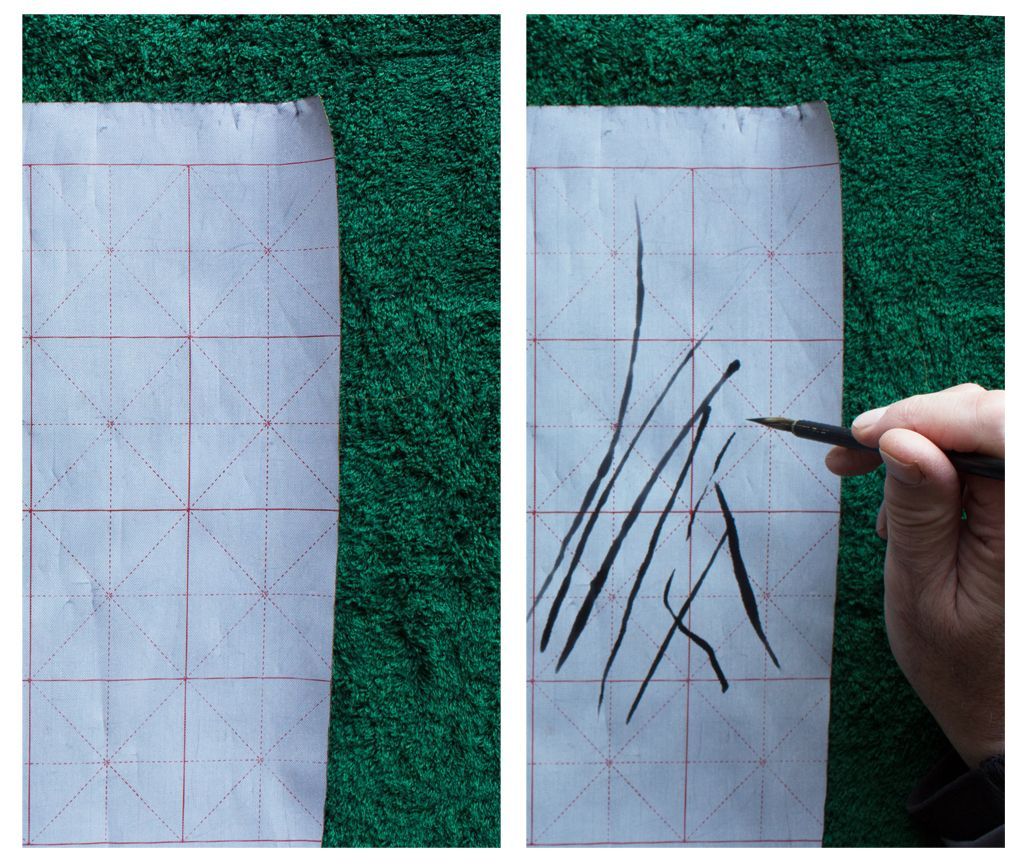

Figure 7: Painting detail with the short-haired brush.

Figure 8: Painting lines with the long-haired brush.

Both the short-haired and long-haired detailing brushes are easy to paint with and offer good control, as can be seen in figures 7 and 8.

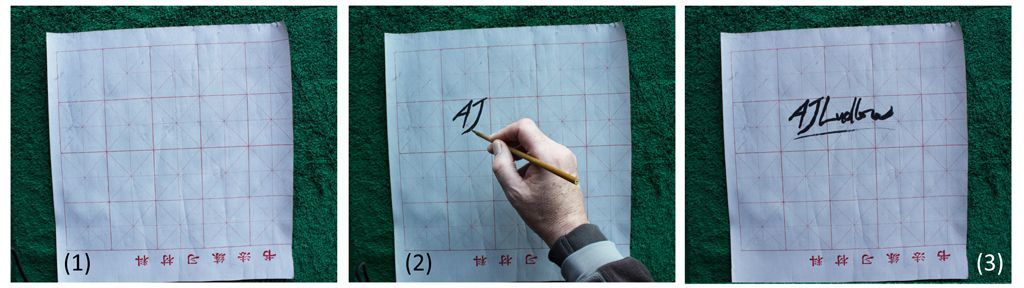

To further test these Chinese brushes, I decided to use some of them to paint with my watercolours (A J Ludlow Professional Watercolours) on hand-made watercolour paper (see figure 9). I used the different brushes for different parts of the painting; the mixed hair large calligraphy brush for the background wash (figure 9(2)), the medium mixed hair brush for the bulk of the painting of the seagull (figure 9(3)) and the short-haired detailing brush to add in the final details (figure 9(4)).